Bournemouth University’s new career frameworks for academics are the subject of a longitudinal study funded by the Innovation and Transformation Fund. In this blogpost Matthew Bennett highlights some of the learning gathered to date.

In theory academic career frameworks have a critical role in the delivery of institutional strategic objectives, in creating effective and efficient employees, as well as balancing competing pressures on academic time. Getting it right matters, and has implications for the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of higher education.

Career frameworks are inclusive of such things as: job descriptions and person specifications; promotion routes, criteria and processes; mechanism of pay and reward; and also the development opportunities available to support these processes. Bournemouth University (BU) introduced a new academic career framework in 2014 providing an opportunity for a longitudinal study into the impact of changing a career framework.

This longitudinal study has been made possible by support from the Innovation and Transformation Fund (ITF) and the project is in two parts. The first part reported in the autumn of 2015 and drew on the BU experience in introducing a new career framework and placed it in a sector-wide context, to draw out the learning opportunities for all. In the second part, to be delivered finally in 2018, we will report on the longitudinal case study established in 2015. Some of the key learning from both the BU case study and from the sector are summarised here and in later blog posts:

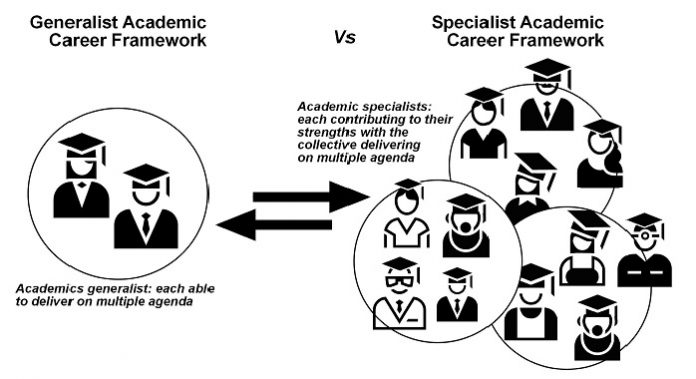

- Specialist versus generalist career frameworks: This is a crucial decision from the outset, and depends on an institution’s long-term financial health and strategic direction. A more generalist approach can reduce risk both institutionally and for staff themselves and provide students with the benefits of working with academics who are engaged in all areas of education, research and practice. It also creates flexibility within the workforce and is likely to be more cost-efficient. There is a real, and perceived, risk however, that staff become too general to be able to perform at the highest levels and devote the time needed to compete, for example, internationally at least in terms of research. You can read more about this in the report and future blogposts.

- Strategy dance. Strategic stability matters in the context of career frameworks and there is an argument to be made that a career framework should perhaps be sufficiently robust to outlive short-term institutional strategies, especially in times as turbulent as those in UK higher education sector at present. <

- Evolution versus revolution: Clearly any change to staffing structures have the potential to cause anxiety and concern for the academics affected, both in terms of their institutional chances for progression, but also their sector-wide mobility in the future. This is why many institutions have adopted evolution staffing strategies, rather than going for revolution. The consequence, of course, is that staffing policy and process may never perfectly align with an institution’s strategic goals.

- Communication and the ‘hurry-up and wait’ syndrome: For the majority of academic staff in an institution, introducing changes to its career framework is likely to be characterised by something akin to a process of: ‘hurry-up and wait’. Essentially, staff are asked to give their feedback over a short period of time and then wait, before being consulted again, and again asked to wait; and so the process proceeds. Negotiations with staff representatives and unions takes time and can’t be rushed, yet for the majority of staff these periods represent episodes of extended waiting with the potential for uncertainty. Managing these periods of ‘waiting’ is critical to the process and keeping the staff base on side.

- Neutrality of leadership: Neutrality of leadership is important in ensuring that one or more types of academic activity is not perceived as being more important than another, unless that is the stated intention. Academic leads for this type of project are typically PVCs or DVC, the workhorses of strategic change, but they are not always seen as neutral leaders as they normally having responsibility for one, or more, strategic areas.

- Implementation: Implementation is everything to the success of changes or modifications to academic career frameworks. The infrastructure needs to be in place and investment made in translating negotiated and approved policy documents into staff-accessible guidance with numerous exemplars to facilitate the smooth running of new processes and approaches.

The full report has more detail on these key conclusions and is a good read for anyone contemplating revolutionary change to an academic career structure. For more details contact Matthew R. Bennett, professor of environmental and geographical sciences at the University of Bournemouth.

The Innovation and Transformation Fund (ITF), supported by the Leadership Foundation and Hefce, stimulates projects to unlock and share good practice in order to advance efficiency and transformation across the higher education sector. The nine projects for 2014, focusing on engaging the higher education workforce in process review, performance and career management and development, are nearing completion and will be shared over the next few months.